Let’s agree that the guitar, despite the glories of the past fifty or so years, is still in its infancy. So, isn’t what it was, nor is it what it will become. It couldn’t be. The guitar has evolved not only in the way it’s built but also in the way it’s played. And what might once have required a big, voluptuous archtop can easily be done with a bolt-neck slab and some modeling gear. Still, it’s nothing to worry about. After all, it’s the music that matters.

Music, though, can fool even the most eager listener. Why? Because to appreciate music–really, to understand it–we first try to define what it is. That’s a benefit, but it’s also a bias. But when you find something you can identify with, it becomes something you crave. You’ll want to know more about it. That’s the case with jazz guitar great John Abercrombie. It’s amazing to think that in his playing one can discern the influences of so many great players yet immediately tell, from the very first note, that none other than he could be playing.

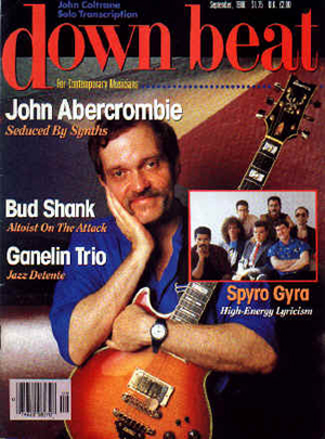

John Abercrombie on the cover of DownBeat Magazine

“Probably the first important guitarist I listened to was Barney Kessel,” he says. “He was the first ‘jazz’ guitarist I ever heard. At that time I was trying to make the transition from blues, rock ‘n’ roll, and R&B players like Chuck Berry. Still, Kessel had a really twangy sound. It was a funky, bluesy, even country kind of sound.”

It was a constant drive . . . a hunger. There was so much to hear, and so much to learn. As a young man, Abercrombie listened to everything he could get by artists such as Jimmy Rainey and Tal Farlow, the latter of whom was considered something of a phenomenon in his day. “Eventually I was fortunate to hear George Benson, and he was just terrifying. And then I heard Pat Martino, and Kenny Burrell.

“But then I heard Wes,” says the guitarist after a short pause. “There was something so natural about the way he played. I used to see him play all the time, back in Boston. I could sit and watch him all night.”

The drive to play–to understand, explore and perfect–hasn’t diminished. The quiet, working-class guy with the moustache continues doing what he does best, as a composer of singularly moving music and a player of the first order.

John Abercrombie was born in December 16, 1944 in Port Chester, New York. Port Chester is sandwiched between the town of Rye (think Barbara Bush) and Greenwich, Connecticut (try not to think of Martha Stewart), two of the ritziest enclaves on the Eastern seaboard. It was the latter place that John called home, though his wasn’t the kind of neighborhood where caviar was standard fare. As he puts it, “I came from the slums of Greenwich. Believe me, there are working-class neighborhoods in all the upscale towns around that area.”

Neither was it a particularly musical household, he says. “In fact, there was no music in the family. My parents liked music, and they bought me a record player, but they didn’t listen to jazz or classical records. Just the radio, maybe, but it wasn’t an important part of their lives.

“The music was just in me,” he adds. “I was into R&B, rock ‘n’ roll, and all that. But as I got a bit older, I decided I wanted to really study the guitar. My parents supported me in it, since they knew I had a good time playing. But then I got really serious, which sort of scared them. I mean, coming from a small town in the late 1950s and ‘60s, and deciding I wanted to go to school and study jazz? Nobody even knew what it was, much less anyone coming from a small town. It was a strange time.”

The avenues were limited in terms of formal jazz studies in the early ‘60s, but they were even more limited for anyone wanting to become a jazz guitarist. After all, the pop phenomenon was relatively new, and the six-string had to overcome a considerable credibility problem. So, John had just a couple of choices, one of which was the Berklee College of Music. Luckily, he was young enough to indulge his dream and give it all the energy it required. If it didn’t pan out, it didn’t pan out. So, once he graduated from high school in June of ’62, he headed up the coast to Boston.

He breathed deep the atmosphere of this earthly jazz heaven, and after a few years he received a diploma certifying him as a musician of professional standing. But he had little interest in making a hobby of the guitar. He wanted to gig, and he’d trained like an athlete in order to do so. Eventually the opportunity came, in the form of an audition for one of those jazzy, funky R&B units that populated the club circuits in cities of the period.

“It was around ’67,” he says. “During my last year of school I hooked up with an organist named Johnny ‘Hammond’ Smith. I was all set to audition for him, and I was really excited, because this was going to be a real jazz gig playing a selection of stuff every night. You had to be able to comp and solo, and do the R&B stuff. It was a great experience. I had to learn lots of songs and get up onstage and play, night after night. Of course, my schoolwork had started to suffer as a result, because I’d realized that this was the real school.”

The guitarist made his first professional recording–an LP called “Nasty”–with Smith in ’68. The band consisted of Smith at the B3, Houston Person on sax, and Grady Tate on drums. Abercrombie toured with the band for a year-and-a-half, playing a gritty, crowd-pleasing mix of tunes. But this was a time of significant cultural change, during which the youth of America, inflamed by their forced involvement in a war overseas and by the exposure of political corruption and corporate collusion, took to the streets and campuses in protest. This could be heard in music, too, most notably in the ferocious guitar playing and poetical psychedelic blues of Jimi Hendrix, who had gone to London in the mid-‘60s and come back as a bearer of the Freak Flag for millions.

“The fusion thing had started to happen,” Abercrombie says, “and all the musicians were listening to Hendrix. Around that time I joined a fusion band called Dreams, which was fronted by the Brecker brothers with Randy on horn, Michael on sax and Barry Rogers on trombone. Billy Cobham was on the drums. The band was holding try-outs, hoping to find a guy who could play rock guitar. So, I went down and auditioned. I’d grown up playing rock and R&B, I’d studied jazz at school, and I’d played all sorts of stuff with Johnny ‘Hammond’ Smith, so I felt pretty much at home with what they were trying to do. They gave me the spot, which was great. I was even going to switch guitars. With Johnny I’d been playing a Gibson L5, but with the fusion stuff it had to be a Les Paul.”

It seemed the guitarist wouldn’t be leaving Boston anytime soon, at least not with all the contacts he was making. But even though Boston is a bona fide metropolis, it’s still a New England city, small by world standards. That meant only one thing: Eventually he’d have to take that first bite out of the Big Apple. The ticket to Gotham arrived in the form of a gig with Chico Hamilton. John moved into an apartment there with his girlfriend, and he quickly found that the spot in Hamilton’s band meant he’d be writing too.

“That was my first professional experience writing music,” Abercrombie explains, “because Chico didn’t write anything. But he’d played with Larry Coryell and Gabor Szabo, and he really liked guitar players. I was still young and full of testosterone, and I wanted to get in there and really do it. I played lots of notes, and I used lots of distortion.”

Abercrombie was by that time identified as a part of the Brecker Brothers scene. But a new group was being put together by heavyweight drummer Billy Cobham, again featuring Mike and Randy on sax and horn. “It was interesting that Billy would give us all a call. That was going to be the Billy Cobham Band, because the Mahavishnu Orchestra was breaking up and his plan was definitely to continue playing. Now, when this guy played, you knew it. And when we played, the decibel level was so intense you could see it. It was frighteningly loud.”

Abercrombie, though, hadn’t forgotten what he’d set out to be in the first place: a jazz guitarist. To him, the Billy Cobham Band wasn’t a jazz group but a variation on the fusion motif. “There was no emphasis on harmony,” he says, “and there was basically no jazz rhythm. Looking back at that time, I think of the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Weather Report as the two most listenable groups of the genre. Of course, all those guys had played with Miles, and with Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter in there, Weather Report had a great deal of harmony. I think that was probably the most memorable music of the whole fusion period. The rest of it, even though it involved some amazing musicians, didn’t interest me. It was way over the top, like a circus.”

Fate stepped in again. Abercrombie’s reverberant tone, so somber yet brimming with emotion, had caught the attention of another gifted young guitarist: Ralph Towner. “I got together with Ralph in New York,” he says. “In fact, he’s the one who got me together with ECM Records. He’d done stuff with [Norwegian saxophonist/composer] Jan Garbarek, and also with [German bassist/composer] Eberhard Weber. I started meeting all these people, and one day Manfred Eicher [founder/executive producer of ECM] asked me to make a record. Manfred had heard me play on a record I’d done with an Italian trumpeter named Enrico Rava, and apparently there was something in my playing that he liked. First he recommended that I do a couple of things with [soprano saxophonist] Dave Liebman, and then he said, ‘I think you’re ready to do your own record.’ I certainly didn’t feel that way, but one day I just sat down and started writing some tunes.”

A sound was beginning to take shape in Abercrombie’s head, and part of the concept involved the polyrhythmic approach of his good friend Jack DeJohnette, the brilliant jazz drummer. The two got in touch, whereupon Abercrombie also called up a former roommate, the Czech keyboardist and Mahavishnu alumnus Jan Hammer. “I told Jack and Jan, ‘This is how I want my record to be, with an organ sound . . . . ‘” The result was Timeless, a set highlighted by intense improvisations and slow, moody tone poems. But Timeless was more than simply the newest rung on the ladder for a fast-rising guitarist. It was an artistic success that brought enthusiastic response from lovers of jazz, fusion and new music. Here was an electric guitarist who could play in a trio with the likes of Hammer and DeJohnette, who could contribute significantly as a composer, and who was enough of an individual to resist sounding like yet another John McLaughlin imitator. The feeling was of someone very new, yet of someone who had been around. From the first groove of the record, Abercrombie had stepped into the upper echelon of modern guitardom.

“Timeless was the first recording under my own name. I wrote about four of the tunes on it, so at that point I realized I had a knack for writing. Actually, I hadn’t done much of it until that record. This got me into writing more, and eventually having my own band.”

It was a time when the guitar was the measure of musicianship. Perhaps it was unfair even to him, but with Timeless Abercrombie had set the bar almost too high. How could he hope to follow it? The answer was simple: Do something different the next time around. So, he recorded Works, a solo collection resplendent in layers of John’s now-classic sound. Like its predecessor, it offered a trademark blend of harmonic sophistication and remarkable single-string technique. Indeed, Abercrombie’s style and approach proved a perfect match for the “ECM sound,” which conveyed a heavy sense of solitude through the use reverberation and other ambient techniques. This isn’t to say ECM ever pandered to the music-as-wallpaper crowd. The ECM label welcomed diversity and change, but it’s safe to say it wouldn’t put out the welcome mat for weeny players. Being the creation of a musician who was equally skilled as an engineer, and populated with a stable of gifted European and American artists, it stood out as a venue for those who sought more from music than what the usual, market-driven categories could offer. So, Abercrombie–having started at ECM with a trio before going solo–returned for his third outing with a quartet featuring Ritchie Beirach on keyboards, Czech bassist George Mraz and Peter Donald on drums.

“I had become a leader at that point,” Abercrombie says. “It was the mid ‘70s, and soon we were touring Europe and the States. The band continued until the early ‘80s, but by that time I’d hooked up with [drummer] Peter Erskine. He was moving back to New York from L.A., and he said we should get together. On a free night we went down to hear the Bill Evans Trio, which had Marc Johnson on bass. Hearing Marc just blew my mind. I was floored by his playing, and he said the feelings were mutual, which I felt was a great compliment. So, Erskine, Johnson and I put together a trio, and at that point we got into more of an electric style. I started using a guitar synthesizer, which a lot of people seemed to think I should never have done. The band lasted four or five years. My quartet had made four records for ECM, but ultimately this trio made five.”

The Hammond B3 organ is arguably the most imitated electric keyboard on the planet. Not surprisingly, Abercrombie, who had come up in Johnny “Hammond” Smith’s band and then featured the organ on Timeless would want to keep the vibe going. However, it would mean another change in personnel, and an end to the trio with Peter Erskine and Marc Johnson.

“I really wanted to do something with the organ, ‘cause I’d always loved that sound. I had an old friend named Dan Wall, who said he’d like to do something with me, and I had another friend named Adam Nussbaum, who’s a great drummer. (I know a lot of great drummers.) So, the new trio became an organ trio.” Two studio records were produced, followed by a live set.

Jazzers seem so accustomed to their lot. Apparently they think nothing of grouping, disbanding, regrouping, recording and renaming. And while others might think of it as a liability or a barrier to the achievement of a good old-fashioned reputation, for these guys it can mean a degree of freedom they wouldn’t have otherwise. Hell, if you’re good enough to go from standards to meterless improvisation, who’d try to stop you? Thus Abercrombie, by welcoming prodigal string players and percussionists alike, has achieved longevity in his career and diversity in his musical output.

Now It Gets Personal

Abercrombie is known as much for understated melodic embellishments and soft yet persistent vibrato as he is for the sound he gets with his guitar. Where one artist would favor a very dry, very present sound–or where another might employ a touch of slapback to give it some projection–Abercrombie seems to play the room rather than the amp. His sound, which originates at the soundboard soft and muted, reaches the listener’s ear through a complex series of reflections, so that there is as much “air” in the notes as there is attack or decay. Well-known players from contemporary jazz and the studio world have made big money with the help of chorus, shelving and other time-delay techniques, but Abercrombie’s sonic palette stands apart for its purity and sincerity. Even when he rocks, it still manages to sound beautiful. So, where did he get such a rich, echoing sound? It’d be easy to assume he picked it up in church, or amid the hallways and high ceilings of some cavernous old house. But that’d be wrong.

“I could never have found that kind of sound in our house,” Abercrombie says. “My bedroom was tiny, and the room I used for practice was little more than a closet. But when I was young I had a teacher named Bill Frienz. He’d come over for a half-hour, and he could play some jazzy things. One day he came by with this little reverb unit. We tried it out, and it was such an attractive sound. From that point on I was really taken with the spaciousness of the way things could sound. That’s what I like about some of the old Miles records. You could tell they were getting a bit of reverb, even though it wasn’t a lot. This little Fender thing was amazingly cool. Still, in those days there wasn’t much of a choice in terms of amps. There was tremolo, but nobody really used it except to play like Duane Eddy. You had nothing to compare to, so you just relied on your amp. Most of my amps had spring reverb, which I always used. So, I guess you can blame it all on that.

“Years later I got an Echoplex, but I never really figured out how to use those things. I remember the first digital reverb I came across. I was working a gig in Munich, and everybody knew how much I loved reverb. Somebody suggested I try a unit by Dynacord. I went down to the local music store and plugged it in, and immediately I had to have it. It cost everything I was going to make that week. I still have it, in fact.”

Abercrombie credits his love of echo to the fabled Fender design, with its tube-driven signal path and integral springs. According to Keith Gregory at Gruhn Guitars in Nashville, that would be a “Fender Reverb Unit.” Introduced in 1961, the Reverb featured a brown Tolex covering with a flat logo and a leather handle. The face panel was also brown, as were the knobs and a plastic domed switch. It incorporated a two-spring pan and a footswitch with a ¼” jack.

The amplifier is somewhat less critical in the equation. For lives dates Abercrombie will usually request a Mesa-Boogie or a Roland Jazz Chorus. At home he routes his signal through a Mesa-Boogie preamp and then into a Walter Woods stereo power amplifier, and then augments it with a Boss SE-50 reverb and a multi-effects unit.

“For a while I was so involved with synthesizers that it became an obsession. But eventually I had to get away from that, because the sound started to feel very synthetic. Basically, I gave all the stuff away, but I still have that Roland GR-300.”

A Unique Choice of Instrument

The soft yet persistent tone so readily associated with John Abercrombie is more often obtained through use of a solid-body guitar than a semi-acoustic or full-bodied archtop. That shouldn’t be so surprising, though, since the modern solid-body has undergone a considerable degree of scientific analysis and artistic endeavor, resulting in a number of instruments that are more playable and more accommodating than their predecessors. Abercrombie’s choice, then, is a Brian Moore DC1. “Basically, it’s a Les Paul style of guitar,” he says. “I tend toward a solid-body, Les Paul sort of sound, anyway. I have an Ibanez solid-body, too, and a Tele-style guitar by Roger Sadowsky.”

He still loves a good archtop, though, as is clear from his descriptions of two key instruments: “I have an old Gibson ES-175 from the late ’50s. It needs serious work, but it’s definitely the guitar I’ll never sell. I also have one made by Jim Mapson, out in California. It’s a little, shallow archtop, and that guitar is probably one of the most amazing ones I own. I can’t play it real loud—there’s a limit to how far it will go–but it has one of the fattest sounds I’ve ever heard.”

About the Music

If Abercrombie’s sound and touch succeed in evoking a sense of place, then the music he plays is equally a part of that success. With Abercrombie there is no discussion of a particular piece being assembled simply for the purpose of giving the players “a chance to show off their chops.” Despite his easy affability, there exists in Abercrombie a fierce drive to explore the inner environs of his imagination. After all, this isn’t kid stuff. This isn’t guitar for the sake of itself, in which the instrument’s make and model matter as much as anything else.

Asked whether he’d describe himself as primarily a guitarist or composer, Abercrombie says, “I’m a little bit of both, really. Jim Hall once said he was ‘a musician who happened to play the guitar.’ I feel that way, too. But he’d agree that we’re all still guitarists. I think you have to work at it, to a certain extent.”

The pull of jazz and its harmonic vocabulary is such that it leads Abercrombie to say, “I’d love to do an album of standards and play them kind of straight.” But he could easily go that route, having demonstrated his facility with chord melodies in the trio format. Still, his personal mode of expression isn’t so traditional. “When I compose, I don’t create music that’s straight. I have to follow my train of thought. Ultimately, I look at it as a positive thing, ‘cause I can go in any direction I want. Other guitarists might say, “Oh, that’s Abercrombie. He’s crazy, so he can just go with what he feels like doing.” That doesn’t mean there’s any less work involved, since I have to try and follow my own creative impulse rather than rely on what has come before.”

A Personal Ethic

Given the very personal nature of Abercrombie’s music, one might expect him to shy away from requests to share his knowledge. Actually, though, he teaches guitar at the college level. To Abercrombie it’s really more about the mind of the musician. And in the long run it’s more practical than what you’d get from a school of hot licks.

“I don’t have any specific goal when I teach, really,” he confesses. “You know, I try to give my students things that are helpful, encouraging or even disillusioning. I try to get them to play a little more like what they really hear, which means they have to play less. They have to think about the chords, not the scales. That lets them hear the music regardless of the changes in key.

“Playing less is actually very hard for the students to do, because they’re often too busy thinking about scales. That kind of habit can get you into big trouble. I find that rock players can use the scales more than jazz players, ‘cause they’re not playing through different keys. They’re thinking in terms of modes. But in jazz, if you start playing the notes of the scale, it sounds kind of funny. You have to go back and start thinking about the chords.”

All in the Wrist

An understanding of chords and their implied movements is certainly apparent in Abercrombie’s playing. Few other guitarists can delineate the structure of a piece with such admirable economy, and fewer still can give it such a beautiful sense of nuance. In his playing nothing is wasted, nor is there any allegiance to lounge riffs and pentatonic fluff. Instead you’ll find a sense of melody that enhances the perception of harmony and dynamics. His vibrato is certainly part of that. As much a classical rubato as the thumb-hinged grasp of blues origin, it’s remarkably fluid and personal. Added to that is a technique of relaxing the note from a whole-step bend or even a minor third. All this serves as a form of sonic signature, expressing his reverence for emotion.

So, what makes Abercrombie’s playing so approachable despite its depth and sonority? How is it possible to make a single note linger in memory for years? Perhaps it’s the patience that is so evident in his approach. Here the listener can readily sense the infinitesimal offset between the right and left hands, which, following on the slight muting of notes as they’re fretted, makes every sound one that’s eagerly anticipated.

“I think many musicians are aware that they have to be entertainers. So, with fusion stuff and the music that came later, there was an element of athleticism involved. There’s less of that in jazz music, or at least certain forms of it. Jazz playing in general requires a level of interaction, but a good fusion player wouldn’t necessarily have to do that. You could have blazing technique but not have to interact with the drummer. But with jazz, it becomes really obvious if you can’t relate to the rest of the band.”

The Point of Arrival

He may downplay his own technique, but there is a wealth of wisdom in Abercrombie’s playing. What’s apparent is that the knowledge of chords, the ability to compose and other skills acquired during his years in school have been refined over the course of a career as one of the finest guitarists in modern jazz. Abercrombie has managed to transcend the traditional approach to his idiom and reached a point where the physicality of playing the guitar becomes transparent.

“I’ve always gravitated toward horizontal playing,” he explains. “That’s how you can get places and play more melodically. I think of the guitar as a voice from bottom note to top. I was always taught based on positions, but I realized early on that alternate picking wasn’t the way I should go. I practice scales a lot, and I have a way of sliding between positions in the same scale without a lot of effort. So, you can learn where all the notes are on all the strings, but when you improvise on a chord progression using only one or two strings you can play more melodically without having to move across all the strings.”

The concept says a lot about the Abercrombie began his musical life as a guitarist rather than moving from another instrument, as so many others have done. Listening to those lines, which can burn in the mind yet just as readily elude the hands, it’s clear that the notes are meaningful as individual events and as components in a chord structure. It’s a quality that sets his guitar apart from other instruments.

“The only time I think more like a piano player is when I play chordally, as when I comp by using my fingers to pluck all the notes at once. Actually, I think of counterpoint more in terms of question-and-answer. I’ll play a phrase and then answer it with another phrase or line. They’re contrapuntal, but they’re not happening at the same time.”

It’s abundantly clear to John Abercrombie that to play well the guitarist should listen to the conversation going on between the other instruments in the group. Don’t play too much, he says. Stay off the soapbox until the time is right. Still, you have to be ready to do it. Remember, you’re playing for people who might be casual listeners at best, and at any rate many of them won’t be musicians.

Abercrombie needn’t preach his talents, nor should he play with any less of the economy for which he’s known. Like a Japanese fan once told me, “Basically . . . his music is best.” One need only interpret this to mean that Abercrombie has the brains and good sense to play from the heart. It means he always plays what’s right for the moment. There’s no better testament than that.

Author’s Note: Larry Payne is a professional writer whose work has been featured in Guitar Player, Guitar for the Practicing Musician, Guitar Extra, Virgin Records’ Dogma, Music Connection and many others. He’s also a fluent guitarist and occasional collector of vintage instruments. Among his current favorites are an early ’60s Eko Model 200 small-bodied archtop, a 1984 Yamaha SBG1300TS through-body unit, his custom-made ESP Craft House Superstrat, and his new Eastwood Sidejack.

Asking questions are in fact nice thing if you are not

understanding anything entirely, however this paragraph presents fastidious understanding even.

Wow, marvelous weblog format! How long have you

ever been running a blog for? you made blogging

look easy. The overall look of your website is great, let alone the content material!

my webpage http://www.oraljelly.es